How nice it would be if people who created attractive things were equally attractive themselves. Alas, that's not necessarily the case. Composers, poets, writers, painters, sculptors, playwrights—a lot of them were well-spoken, well-behaved folks who lived blameless lives and left humanity a legacy unstained by misdeeds. Others bequeathed artistic products that resembled nothing so much as lotuses emerging from the muck of fractured personalities or behaviorial abnormalities. The upright, forthright, nice-guy types might be the most admirable, but it's the scumbags who are the most intriguing.

Alessandro Stradella is my poster boy for artists whose brains were mostly between their legs. Born in 1639 to a good Bolognese family and blessed with a first-rate education, he went straight to the top as one of Queen Christina of Sweden's house composers in Rome. Just to keep that in perspective: Arcangelo Corelli was another of her boys. That Christina didn't fart around. She hired only the best. Young Alessandro should have floated from triumph to triumph, winding up with a career as star-strewn as Corelli's. Instead he screwed everything in sight. His preferred bed partners were the unmarried and presumably virginal daughters of Roman noble houses, a practice sure to land him on a lot of shit lists. He added to that an unsuccessful attempt to embezzle a pile of money from the church. Before long he was out of Rome for good, barely in time to avoid spending the rest of his lusty youth in a dungeon.

Stradella screwed, gambled, and borrowed his way around Italy, all the time writing oratorios, operas, and on the side helping to establish the new instrumental genre called the concerto grosso. Talent he had in spades. Of judgment and maturity he was conspicuously lacking. A Venetian shotgun wedding resulted, but his father-in-law had a more ambitious master plan than merely snaring Alessandro as unwilling husband for his despoiled daughter. Instead, Daddy Dearest put out a contract on his new son-in-law, and Alessandro was duly but unsuccessfully attacked on October 10, 1677 by a pair of apparently half-baked goons. Having survived the assassination attempt, Alessandro demonstrated that testosterone remained his guiding angel, and shortly thereafter he was up to his old tricks in Genoa, writing operas for the local theater, fornicating up a storm, and skulking around with his church-thieving pal from Rome.

From this we may assume that Alessandro was one of those idiots who remain utterly convinced of their immortality up to that last split second before the car carooms off the cliff or the lion charges or the gun goes off. Either Daddy Dearest (Alvise Contarini) tracked him to Genoa, or else another outraged father called in some favors, or else a gang of offended parents, debtors, and detectives compared notes, went collectively nova, and pooled their resources. We'll never know. A second contract went out. Not that hapless duo who bungled the 1677 job, not this time. This time it was a seasoned pro. 42-year-old Alessandro Stradella got himself whacked right in public, in Genoa's busy Piazza Bianchi. So much for him. Corelli and Alessandro Scarlatti get all the attention from posterity. These days Stradella is mostly remembered—if he's remembered at all—as the guy whose music Handel swiped for Israel in Egypt. Once in a while Friedrich von Flotow's opera Alessandro Stradella gets a staging; the focus is on Alessandro's dissolute life and his grisly death, certainly not his substantial achievements as a composer.

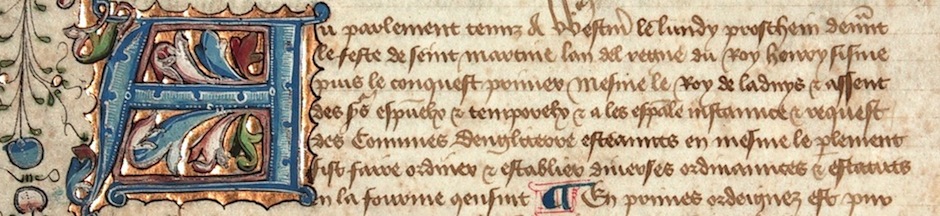

The one surviving image of Alessandro Stradella implies that he was a looker and then some. His wild life makes sense: aristocratic, gifted, hot, and Peter Pan. Too bad he couldn't have held it together just enough to avoid being offed in his prime. So he's a minor mid-Baroque composer instead of the giant he could have been. Ah, well. One gets the distinct impression that he had no regrets. Like Errol Flynn, he was interested only in the first half of life, not in those later greying and relatively subdued years. Thus he remains the mal puer eternale, the gang-banger with the heart of a poet, the lusty rake who had it his way, no matter what the consequences. There's something very cool about that—especially viewed from the comfortable remove of several centuries.