In 1988 a friend and I attended the first run of Martin Scorsese’s film The Last Temptation of Christ. It was playing at the now-posthumous Northpoint Theater, one of the City’s nicest first-run movie houses. It being a popular—indeed, notorious—film, there was a goodly line. We stood there and waited. All the while picketers were marching by with their crude hand-lettered signs denouncing the film as a piece of anti-Christian propaganda. Obviously they knew nothing about the film or its source—a 1953 novel by the devoutly Christian author Nikos Kazantzakis. In fact, there’s not a scintilla of anti-Christian rhetoric in novel or book. The picketers had heard through whatever creaky grapevine they consult that the movie depicted Jesus as marrying Mary Magdalene and having children with her. And so it does, in the “last temptation” sequence—a fantasy in which Satan makes one last attempt to steer Christ off his appointed path. He resists the temptation, and the film ends as he dies in the knowledge that his message has remained untainted.

The protesters in that wan gaggle were a bunch of ignorant clods, to be sure. But they were peaceful ignorant clods. They didn’t throw rocks or garbage or hand grenades, they didn’t cuss us out for buying tickets, they didn’t whip out swords and attempt to behead us, they didn’t fire submachine guns in our general direction. They did nothing to harm the theater. All they did was schlep around and wave their signs as they trumpeted their stupidity to all the world. And that was their Constitutional right.

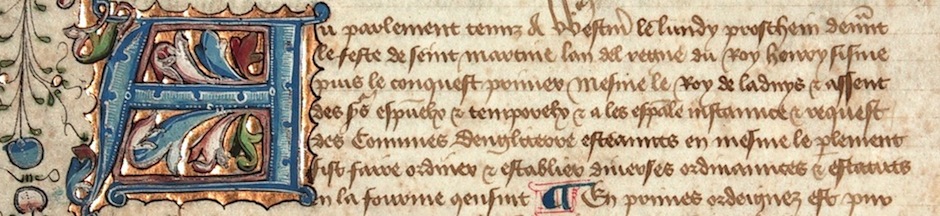

I am reminded of Barbara Tuchmann’s masterful study of the 14th century, A Distant Mirror. Far more than a dutiful recounting of battles or political intrigues, Tuchmann delves into the minds of the people who lived through that tragic century, trying to understand what it was that made them tick. She noted the strange volatility of medieval temperaments. A chap might be calm and reasonable one moment, then ripping the place apart in rage the next. The most trivial slights could, and did, result in long-standing conflicts, even wars, thanks to that inability of the average person to count to one hundred before reacting. There was no impetus for people to learn restraint; those hair-trigger tempers were the norm from king to commoner, nor was there any underlying code of law or conduct that could act as an ameliorating force. A lack of education combined with absurdly narrow provincialism resulted in astounding naïveté and downright flabbergasting gullibility, even amongst the aristocracy. Only with the establishment of democratic governments, republics, and the necessity of consensus was there a chance that grown men might stop behaving with the impetuous recklessness of third graders at recess. Education, cosmopolitanism, culture, government: all came together to bring about a dramatic lessening of volatile bursts in both the private and public sector. That isn’t to say that they disappeared altogether. But we’ve come a long way since King Theobald IV of Rufitania could wake up on the wrong side of the bed and plunge his nation into a ruinous war.

Stephen Pinker, in his recent The Better Angels of Our Nature, points out this fundamental shift in human behavior as one of the signature changes between the medieval and modern mind. We have learned, slowly and painfully, the advantages of thinking before acting. We’ve gotten better at living together, despite our differences. We can shoot our mouths off all we want, but not our guns; one is protected speech, the other is first-degree murder. Even then, our judicial system moves with all deliberation. It takes a lot of steps to dump somebody’s tuckus into jail, a whole lot more to cough up a Sodium Pentothal injection. All designed to ameliorate the lingering effects of anger, frustration, and thirst for revenge.

The slow-cook process that led to the modern Western embrace of tolerance, freedom of speech and religion, and legally sanctioned remedies has come only fitfully, and slowly, to the Arab world. That it will come some day—probably a lot sooner than most people think—is likely. The distressing and tragic events of the past week, as small groups of hotheads have gone nova over the flimsy pretext of an amateurish and hopelessly moronic film, demonstrate that they really need to simmer down and wise up. Clearly the ruckus has little to do with the film itself or even with any perceived insult to Islam. It’s being stirred up by professional agitators who see in the disaffected and frustrated youth of Muslim communities an opportunity to score some political points. Those Arab youth share a great deal in common with their European counterparts in the Middle Ages: a restricted education that focuses mostly on revealed religious dogma, ignorance of other ways of thinking, and a patriarchal culture that stifles both dissent and creativity. Add to that their perfectly understandable envy of Western European affluence and opportunity, not to mention resentment of the disdain emanating from those very Western European countries—some of that disdain enforced with military occupations, invasions, and high-tech drone strikes—and you’ve got a box full of ammunition ready to wreak havoc at the slightest opportunity.

Yet I remain unconvinced that the Western powers can do much of anything about it, save keeping their distance. The West has gone through its own process of growth, punctuated by spurts of energy then nearly stifled by sickening backslides. Yet over time the net sum has been positive, even if at certain times during the past 500 some-odd years one might despair of any hope. A German during the 30 Years War may well have concluded that it was the endgame, and that civilization itself was crumbling. Ditto European Jews during the Holocaust, ditto Europeans during the height of the Black Plague of the 14th century, ditto this and ditto that. But the 30 Years War ended with a Germany that slowly righted itself and entered that amazing efflorescence of the late Baroque. The Black Plague didn’t kill everybody and the Renaissance was under way within a few generations. Hitler failed to destroy all the Jews or Gypsies or homosexuals, and the Third Reich has melted away into a progressive and civilized nation. Change is possible. With any luck—or with a lot of luck—the Arab Spring will turn into summer, and not regress back into a winter of superstition and despair. But even if it does, there’s always hope that the next time around will be a little bit better. I look forward to a day when pissed-off Muslims can stomp along the sidewalk in front of a movie theater while waving signs and making a racket, as people just walk around them, perhaps annoyed but otherwise unconcerned.