If there is one painting I would like to own, it’s Samuel Palmer’s 1839 The Rise of the Skylark. At first glance it seems little more than your basic drippy mid-Romantic idyllic landscape, as the man by the gate gazes upwards into the sunset sky and beholds (and perhaps hears) a skylark in the far distance.

Extended viewing reveals much more. To my mind, The Rise of the Skylark is nothing less than a vision of Eden. The transcendent is made immanent in an already paradisical landscape that offers a glimpse of eternity in its immense but softly glowing sky. The skylark’s realm may seem to be the air, and ours the earth, but it isn’t really like that at all. We are both made of the same stuff, and we belong in the same world. Paradise has no boundaries.

Palmer’s younger contemporary, poet George Meredith, understood the message of The Rise of the Skylark only too well. In his richly evocative The Lark Ascending he wrote:

For singing till his heaven fills,

‘Tis love of earth that he instils,

And ever winging up and up,

Our valley is his golden cup,

And he the wine which overflows

To lift us with him as he goes.

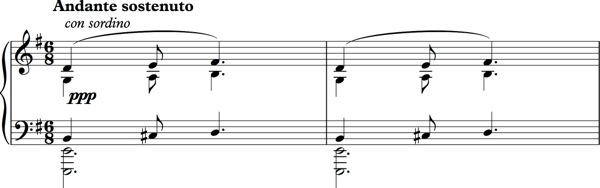

Thus in 1914 Ralph Vaughan Williams was moved to express Palmer’s and Meredith’s vision of transcendence in music. The result was The Lark Ascending, originally cast for violin and piano but best known in its 1921 version with orchestra. Lark therefore spans the signature trauma of Vaughan Williams’ life, the cataclysmic World War that cast a glowering shadow over idyllic pastoral yearnings such as Rise of the Skylark. The War imparts a mood of mourning to canvas, poem, and composition—a lost Eden, ardently loved even as the vision fades away.

Vaughan Williams chose his materials with care. The entire work is cast in various dialects of the pentatonic mode, the perfect choice for such an evocation of innocence. That might require a bit of clarification. Despite its debasement as accouterment to pop culture faux-Chinoiserie, the pentatonic mode is in no way specifically Asian and is, in fact, common coin of all musical cultures no matter what their level of sophistication. The most acoustically fundamental pitches fall naturally into pentatonic scales, thus the connotations of an unspoiled and chaste music, pre-lapsarian if you will. Consider the basic interval of the perfect fifth, in which the ratio of upper to lower pitch is 3:2. Only the octave (2:1) is more elemental, but we hear it as a reduplication of the original pitch. The fifth, on the other hand, is audibly different—thus the first new note to arise after the fundamental.

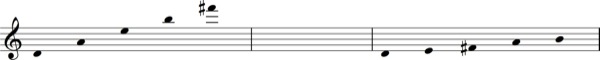

Begin with a D. Add a fifth to the D and you get an A. Continue adding fifths to the note: E above A, B above E, F# above B. Line them up in alphabetical order starting with D, and you have a pentatonic scale:

That is the modal world of The Lark Ascending.

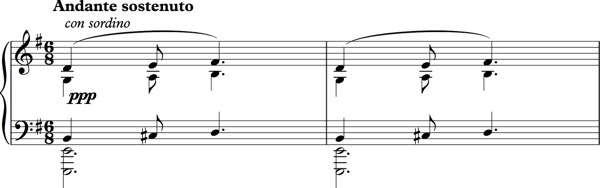

Rhetorically, Lark is a dialog between the solo violin (the skylark, a.k.a. the air) and the orchestra (the earth). The very opening establishes both the interdependence and the apparent separation of that relationship. The orchestra is constructed, harmonic, i.e., earthly. Suave chords built of fifths move in a diatonic parallel motion that occasionally mandates one tone beyond the five—thus the tenor-voice C-sharp, a fifth above F-sharp.

This earth motif will recur throughout the work, as a grounding and centering.

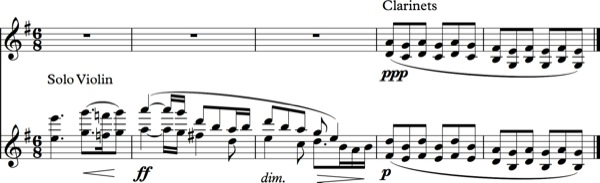

The skylark enters in the first of a series of rapturous violin cadenzas. As we might expect, not only is the melodic line chastely pentatonic and undisturbed by polyphony, but it is also unmeasured. How could it be otherwise? The violin begins low, in the same register as the introductory earth motif.

It doesn’t stay earth-bound for long. Gradually it rises, ever higher, eventually reaching a full three octaves above its starting point. Upon sailing to its highest peak it acquires just a hint of organized melody, a suggestion of a gentle siciliana rhythm.

With that, The Lark Ascending becomes an ecstatic dialog between violin and orchestra, as the lyrical main melody is joined by passages of birdsong, usually in the violin, but the earthbound orchestral instruments also have their sky-borne moments, encouraged and praised by the cascading and fluttering lark.

Each of the Lark‘s three sections ends in a luminous cadence shared between violin and orchestra. Each cadence brings a subtle transformation to the violin, as its monophonic—a.k.a. single-line—texture gives way to double stops, thus bringing earth-element harmony to air-element violin. The union of earth and air is made all the more manifest as paired clarinets join the violin, the three instruments sinking softly to earth in parallel chords.

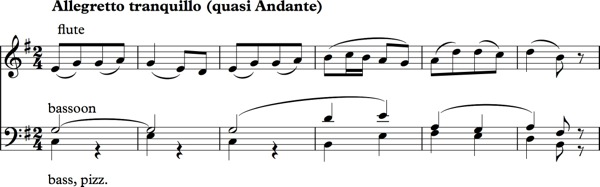

We humans are the protagonists of the contrasting central interlude. Our quotidian world is expressed in a fine, upstanding folk-ish melody, still pentatonic but in a different dialect. The tonic drops down a step to C, underpinning the quietly simple tune with serenely unruffled chords.

The interlude ends in a variant on the closing cadence and soon enough the original section returns, albeit condensed. Lark and earth sing together to their rapturous mutual cadence, and eventually the music settles back to the earth motif, now yet slower and softer.

And the lark ascends. Higher…ever higher. The orchestra fades away, and the world is the skylark, the skylark is the world. We belong to earth and air. Heaven is earth and earth is heaven. The lark ascends…