You might have noticed that many old-style opera houses contain gigantic, ornate foyers. Consider Milan’s La Scala, Venice’s La Fenice, and the Teatro di San Carlo in Naples. Even relatively modern opera houses have tended to crib the notion of the stupendous foyer, as a visit to San Francisco’s War Memorial Opera House will make abundantly clear. Not only are the foyers grandiose, but they’re also resolutely shut off from the hurlyburly just outside.

It seems like an awful lot of wasted space. People mostly just pass through the foyer on their way to the auditorium, after all. To be sure, the foyer serves as a milling-about locale, but still one could imagine shrinking the thing down dramatically and getting by just fine. Vide Davies Symphony Hall with its slender glass-lined lobby that minimizes the distinction between inside and outside.

Those massive, ornate, and isolated spaces bear witness to a little-known factoid about old-time opera houses: their foyers were casinos. In addition to being the plutocracy’s favored venue for schmoozing, wheeler-dealing, and showing off, the local opera house was also the local Vegas. Municipal authorities were smart to grant gambling monopolies to theater impresarios, because the river of money flowing in from the lobby casino counterbalanced what was otherwise a notoriously well-greased chute to the poorhouse. All those well-heeled aristocrats didn’t support the opera out of artistic ideals, after all. The opera is where they went to party, and they paid lavishly for their fun, via subsidies, subscriptions, private boxes, gifts, and gambling losses. Some impresarios wound up richer than Croesus. Prima donnas bought themselves Venetian palazzos and Alpine castles. Even the occasional composer—think Rossini—shared in the bounty. All the while, what happened in La Scala stayed in La Scala. It worked.

The über-powerful Domenico Barbaja (1778–1841), who ran not only the San Carlo but also La Scala and Vienna’s Theater an der Wein, made his first boodle as the inventor of cappuccino and and his second as a leading promoter of roulette. His gambling monopoly in Italy during the Napoleonic Era made him filthy rich. Music history textbooks generally cover only his role as the managerial engine powering the bel canto era. Fair enough, given that he commissioned handfuls of operas by Donizetti, Bellini, Rossini, and Weber. But he was also a world-class entrepreneur. As if gambling, coffee, and opera weren’t enough, he was also a leading supplier to the military and a high-stakes building contractor who rebuilt the San Carlo after it burned down in 1816. The guy might have been a near-illiterate roughneck, but he had taste and, even more surprising, scrupulous business morals. Hard-driving, overbearing, and tyrannical, but honest. Fascinating guy, Mr. B., the Steve Jobs of Italian opera.

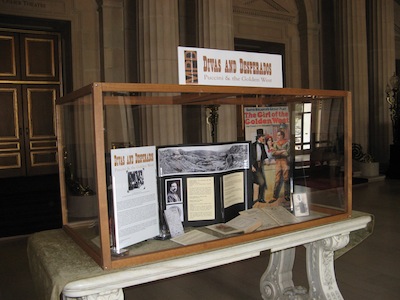

Just imagine rows of blackjack, roulette, and faro tables in the War Memorial Opera House lobby—not to mention a phalanx of (hopefully silent) one-armed bandits over to the side. It will happen when pigs fly, so don’t worry about it. We treat the whole opera-going schtick quite differently these days. Our opera houses, like our symphony halls, are temples and are treated with all due reverence. A few years ago I had a delightful fling as a curator when I created lobby exhibits for the SF Opera’s productions of Puccini’s The Girl of the Golden West and Verdi’s Aïda. Each exhibit was housed in a large Plexiglas case perched on a stone vitrine in the middle of the foyer. Each was popular with the patrons. However, the presiding powers were concerned with what they considered to be ever-increasing clutter in the Opera House foyer, so my Aïda exhibit was, sadly, my last.

Back in Italy, the reaction against opera house casinos started up in the early 19th century, and by 1820 the games were gone. Impresarios were obliged to find other means to finance their productions, and not only did eye-popping spectacles such as Rossini’s Mosè in Egitto become a thing of the past, but the number of commissions shrank. Eventually the local governments stepped in and began providing subsidies. With the Italian Unification, republican spirit brought opposition to public funding of what most people viewed as an upper-class pastime. La Fenice closed down for eleven seasons between 1873 and 1897, San Carlo for three seasons during the 1870s. In the 20th century opera houses passed to the control of directorial boards and became the self-governing, nonprofit institutions that we know today.

So no more roulette. No hookers working the parterre. No hawkers roaming the aisles with booze and munchies. No arrogant fops tossing orange peels out of their boxes onto the heads of the plebians in the stalls.

But you can still get a cappuccino. And the Milanese can still boo a hapless tenor right off the stage, as recently befell an offending schmuck who was obliged to yield mid-opera to his understudy. This is a good thing. As long as folks can get that riled up, we may rest assured that opera hasn’t gone terminally stuffy and pompous, at least not yet.

My Opera House exhibit: maybe someday we’ll do it again.