It’s really a shame that Elgar’s music isn’t better known here in the US. Of his substantial output we get regular performances only of the Enigma Variations, together with the two wonderful concertos—violin and cello. But the rest languishes more unheard than not: the two symphonies, the programmatic overtures, the cantatas, the oratorios, the chamber and vocal works. And yet there’s so much of it that is truly first-rate stuff, not only in relationship to English composers, but to the sweep of Western music in general.

Of late I’ve acquired a penchant for the 1901 Cockaigne Overture, subtitled “In London Town.” (“Cockaigne” is pronounced more or less just as you suspect it might be; George Bernard Shaw suggested that if it bored English audiences, Elgar could change the name to Chloroform.) Cockaigne, written soon after the Enigma Variations and Gerontius but well before the First Symphony, is a product of Elgar’s early compositional maturity. No genteel Victorian London of well-heeled ladies and gents raising their teacups to each other at Ascot, this is a bustling, brawling, noisy, exciting London—and a lushly romanticized one as well, filled with ardor and yearning.

Cockaigne packs a wallop in its brief fifteen-minute running time. Cast in a sturdy three-part form that hints at sonata-allegro, it’s just as much fun to examine for its orchestration as for its varied and masterfully combined materials. There are definitely programmatic elements in the work, but the many themes suggest, rather than depict, their targets and associations.

The “bustle” theme takes on the role of what would be the Primary Theme in a full-tilt sonata-form movement. Note that it carries within it the seed of a descending sequence, in its own descending scale form:

A wonderful transitional theme carries the instruction Nobilmente, the first appearance of this quintessentially Elgarian marking in one of his orchestral scores. The “noble” theme will recur throughout Cockaigne and will, in grand Romantic fashion, provide the final peroration:

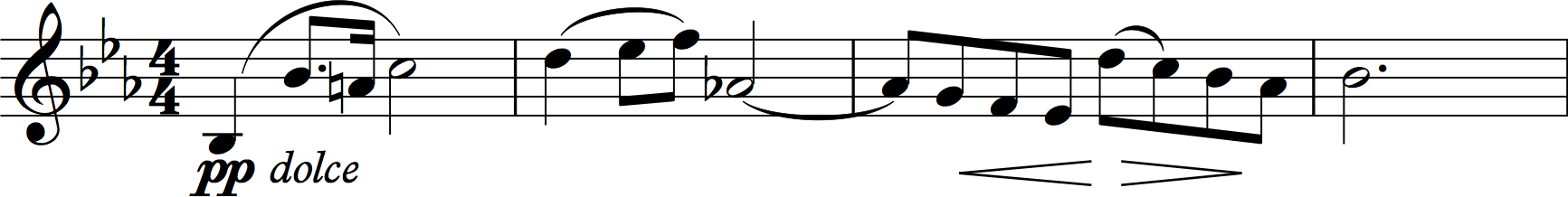

I hear echoes of Die Meistersinger in the “Secondary Theme” proper—most definitely a lover’s theme, young couples perhaps strolling through the parks or along the sidewalks:

Another transitional theme brings to mind images of cheerful street types, Cockneys perhaps, zestily impudent and tripping about with nervous grace. Note that this is actually the “noble” theme, in diminution and made sequential, one of those Meistersinger moments as when the noble masters’ theme becomes the apprentices’ jaunty tune:

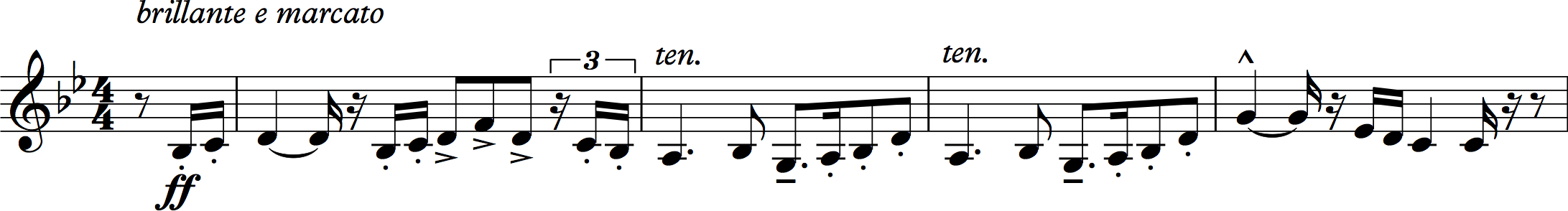

A long build-up leads to the appearance of the gung-ho “Marching Band” passage, perhaps a tad bombastic but glorious fun in its unabashed pomp and energy:

Whew. That’s a lot of stuff. In the quasi-development section many of these tunes are combined, forming a dense weave that evokes a tapestry of associations. With the return of the big “bustle” theme we reach a kind of Recapitulation; the “Meistersinger” theme follows, the Marching Band makes another grand appearance, and then Elgar caps it all with a Cinemascope statement of the “noble” theme, complete with an optional organ part for those orchestras lucky enough to have one. A quick blast through the “bustle” theme, some rousing whacks on the timpani, and it’s all over.

With its frequent mood and tempo changes and potential to blast into sonic overdrive, Cockaigne is a bear to pull off successfully. All too easily it can devolve into travelogue mush or, given too intense of a performance, become strident and overbearing. And yet Elgar’s notation is immaculate and detailed: this is a score with meticulous diacritical markings throughout, all crying out for careful attention. It requires a conductor who knows that the abbreviation ten. over a note means more than just a hold, or that a hairpin <> dynamic might be more than just a casual swell. The dynamics run from ppp all the way through the fff that concludes the first big statement of the “Marching Band” theme, while long-breathed tempo changes require careful stewardship. But throughout it all, there’s something so irresistibly flowing about Cockaigne that micro-managing carries the potential for ruining those long Elgarian lines.

I consulted my (ridiculously large) library and examined a dozen recordings ranging from 1917 to this very year. Of those, three truly nailed the thing—at least in my humble opinion—while only one really missed the mark altogether. Not surprisingly most of these are English orchestras led by English conductors, but there are some exceptions.

Elgar’s Own Recordings

Edward Elgar, the first of the major composers to make extensive use of the gramophone, recorded Cockaigne no fewer than three times. The first dates from February 28, 1917 with Elgar leading a nameless orchestra. Given the pre-microphone technology of the day, in which the players huddled around one or two recording horns, we can expect the sound quality to be seriously compromised, and it is. Cockaigne is written for an XXL-size orchestra, only a subset of which could be used in the recording. Furthermore, the high costs of gramophone discs in those days (as much as $5.00 each, $75.00-ish today) dictated that Cockaigne be condensed down to a single side—about four and a half minutes long. Given that Elgar made the decisions about what and where to cut, the work doesn’t suffer as much as you might think it would from being truncated to a third of its length. Nor is the recording as much of a trial to hear as you might suspect, either. Modern restoration technology has brought out more than its creators ever heard and reveals a chipper, crisp performance, allowing for some dicey moments in the orchestra. That’s understandable under the circumstances. Retakes required taking an entire side at a gulp, so everyday boo-boos were tolerated. Elgar’s 1917 Cockaigne is a delightful rendition, all things considered.

Electric recording brought about a sea change in the recording industry. Orchestras were probably the most obvious beneficiaries of the new technology, since it allowed for an entire orchestra to be recorded with something approaching high fidelity. HMV lost no time getting Elgar up on the podium to conduct his major orchestral works for the microphone. Cockaigne was among his earlier products of the new age, recorded in Queen’s Hall with the Royal Albert Hall orchestra on April 27, 1926. For my money this is the one to cherish: it’s unusually bright (clocking in at a breezy 13 minutes) but avoids any sense of being driven or pushed. It’s just joyous and fast-paced, with plenty of breathing room for the slower spots such as the Meistersinger theme. Maybe the Royal Albert Hall chaps don’t rank in the inner circle of fine orchestra players, but they follow Elgar’s vital leadership and acquit themselves quite well. This is one of the recordings to use an organ in the final peroration of the “noble” theme, quite an achievement for early electric tech.

This is probably the best place to mention that Elgar’s frequently zippy tempi had nothing to do with the limited playing time of 78 rpm discs. Consider that he could have slowed down that 1926 Cockaigne by a good two minutes playing time and still fit on three sides. No less an eminence than Yehudi Menuhin himself testified that the tempi in his legendary 1932 recording of the Violin Concerto were in no way influenced by disc limitations. Those are the tempi he and Elgar wanted. If folks tend to play the piece slower these days, all well and good, but Elgar liked it faster.

On April 11, 1933 Elgar stood on the podium in London’s then-new Abbey Road Studio No. 1 and conducted his third recording of Cockaigne with the also then-new BBC Symphony Orchestra. Although this is the recording that has gone down as the composer’s reference, it lacks the bumptious vitality of the 1926 outing. One must remember that Sir Edward was in the last year of his life. He was tired, ill, and grumpy. Like his younger contemporary Richard Strauss, he was just as capable of stolidly wooden leadership as he was of podium magic. Unfortunately this Cockaigne seems to be from one of those lesser days. The BBC band is more polished than the Royal Albert orchestra, but they lack the other orchestra’s edge-of-the-seat commitment. It’s a perfectly good Cockaigne, to be sure, but despite its dramatically higher level of orchestral skill, it must stand second to Elgar’s jaunty 1926 version. And no organ for the final “noble” theme.

It was HMV’s practice to make multiple wax masters during the recording sessions. Most of the time those were made with a split feed off a single microphone, but every once in a while they used a second microphone with a slightly different placement for the alternate wax master. One of those alternate masters has survived and has been used to create what’s called an “accidental stereo” of the last four minutes or so of Cockaigne. It took a lot of technological know-how to pull that off—speeds and phases had to be matched—but the result is fascinating.

Post-Elgar Mainstream British Conductors

Unusual for a British conductor, Thomas Beecham was never much of an Elgarian, but he did put down a perfectly serviceable Cockaigne in 1954 with his Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. The rendition is neither distinguished nor objectionable. Nothing goes wrong: the tempi are more conservative than Elgar’s but not out of whack in any way. Overall this is a “cool” rendition, but not cold by any means—dig Beecham’s hell-for-leather rendition of the “Marching Band” passages. And Beecham’s Royal Philharmonic simply plays circles around any of Elgar’s orchestras.

Now for a disappointment. One would think that Adrian Boult would give us one of the all-time great Cockaignes. He was, after, a close colleague of Elgar’s and a notable interpreter of his major works such as the symphonies. The recent EMI edition of his complete Elgar recordings tops out at a whopping 19 CDs. He left us four recordings of the Enigma Variations alone. He’s one of the very few major conductors to take on an almost-forgotten ballet, The Sanguine Fan. But Cockaigne would appear to have been off his radar; he left us only one recording, made in All Saints Church in 1970 with the London Philharmonic Orchestra. While the performance is blessed with a gorgeous recording by EMI’s ace engineers, it’s an altogether sloppy and uncommitted reading. Elgar’s meticulous markings might as well have been erased from the score, with only the broadest tempo changes acknowledged. The orchestra plays professionally enough but one gets the distinct impression that perhaps this most skilled of sight-reading orchestras was playing with little or no rehearsal. Heck: the players must have known the piece well enough (what British orchestra doesn’t?) but they just plough through.

Let’s balance disappointment with vindication. In my opinion John Barbirolli never gets his due, especially by American critics and listeners. Maybe it was that unhappy tenure at the New York Philharmonic that did it. Besides, Barbirolli’s home-base Hallé Orchestra wasn’t all that great back in his day, unlike the sterling ensemble it has since become. But Barbirolli was a hell of a great conductor, and his 1962 Cockaigne at the head of the august Philharmonia Orchestra—Klemperer’s Philharmonia, Karajan’s Philharmonia—gets my vote as the finest of them all. The pacing is less quick than Elgar’s (it’s two minutes longer than the 1926 version) but never drags. Barbirolli doesn’t overplay the yearning in the Meistersinger theme but allows for it to breathe fully, and in the loudy-rowdy parts, such as the Marching Band, you can almost see the gentlemen of the Philharmonia grinning from ear to ear. It doesn’t hurt that Barbirolli had London’s acoustically glorious Kingsway Hall for his recording venue. No organ at the end, but I guess you can’t have everything.

Another triumph, albeit of a different sort, comes from Jeffrey Tate at the head of the London Symphony Orchestra in 1991. I tend to think of Tate as a Mozartean and chamber conductor (he was head of the English Chamber Orchestra for fifteen years) but here he brings his always meticulous musicianship to a work which some might treat as a mere crowd-pleaser. The result elevates Cockaigne to a level of expressiveness and innate dignity that even Elgar might have found surprising. This is the slowest Cockaigne on record (17 minutes!) due to the loving care lavished on the slower melodies, not only the Meistersinger and “noble” themes, but also the middle-section tapestries of interwoven materials. There’s plenty of fire in the “Marching Band” sequence—and boy, does it ever strut!—and the use of the organ in the final peroration is simply stunning. In short, this is some kind of a desert-island Cockaigne, perhaps not to everyone’s taste; some might find it micro-managed. But I love it. And who couldn’t admire a performance of such obvious commitment? The LSO’s playing is simply beyond criticism.

Mark Elder and the Hallé came up with a Cockaigne in 2002 that combines luminous orchestral tone with exquisite pacing and a richly sympathetic approach. I’m a big fan of today’s Hallé, an elegant orchestra that’s capable of serious sizzle when necessary. The Elder/Hallé of the Elgar First Symphony is my go-to recording of choice, its sweetly tragic rendition of that work’s magnificent Adagio in my opinion the most moving of them all. Certainly their Cockaigne strays far from Elgar’s own more direct, almost earthy renditions. But there’s a great deal to be said for this eloquent, if slightly cool, performance, with a grandly sonorous organ in the final peroration.

A much rowdier approach can be experienced in Alexander Gibson’s knockout romp with the Scottish National Orchestra, recorded in 1983 and a mainstay on the Chandos label ever since. And with good reason: Gibson stays much closer to Elgar’s zesty spirit, but unlike his noble precedessor he has a truly crackerjack orchestra at his disposal. Coming on the Gibson/Scottish immediately after Elder/Hallé is a bit like running to a big party downstairs after a posh afternoon in the airy upstairs: even the sonics of the recording are appropriately brighter and edgier than the Hallé’s gorgeously cushioned engineering. Cold beer, perhaps, after vintage champagne. Both wonderful.

Mad Max Solti

That Hungarian firebrand Georg Solti, normally a peerless judge of musical pacing, drops the ball quite badly with his 1976 Cockaigne, recorded with the London Philharmonic Orchestra. At least the LPO players are more on their mettle than they are in the easy-going Boult performance of six years earlier, but Solti over-drives them to the point of near-chaos at times. Although there are some very fine passages, overall this is a distressing Cockaigne—more New York than London, and New York on a particularly frenetic day at that. Even the passionate parts are overdone, pushed to operatic shrieking. The Marching Band comes off sounding more like an invading army than a jaunty red-coated Coldstream Guards regiment, and the final Nobilmente peroration is more slugged out than sung. Sad. Solti’s rendition of the First Symphony is one of the better ones in my opinion (although the last movement does become a scramble at times), but this is not a Cockaigne to recommend.

Two Recent Offerings from non-British Conductors

We have two Cockaignes from today’s younger conductors at the head of their respective orchestras. Vasily Petrenko has completed his Shostakovich cycle in Liverpool and so now would seem to be heading towards things Elgarian. A brand-new Cockaigne (coupled with the First Symphony) is an excellent performance in the Beecham sense: utterly professional, polished, but not necessarily distinguished from its counterparts. There is no faulting the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic, which has evolved from fine regional orchestra to a secure place amongst England’s finest bands. And there’s really no faulting Petrenko either; he’s a masterful conductor with a vivid podium presence. It’s a good performance, period. Excellent, even. I haven’t been able to warm up to it all that much, though. Maybe it’s just a little too coiffed.

To wrap things up we have the 2014 outing from the Finnish conductor Sakari Oramo at the head of the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic. Thus Cockaigne escapes its English roots somewhat—although Oramo served as music director of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra up through 2008 and is now in charge of the BBC Symphony. Thus he’s not quite as non-English as he might seem on the surface. Oramo and the Stockholm band give a sturdy performance, also in Beecham mode with its rock-solid technical mastery. For this listener, the recording’s stellar audio (in high-definition digital, no less) does not compensate for the just-the-facts-ma’am literalness of the performance, although the orchestra itself plays flawlessly, as one would expect: the Royal Stockholm is a seriously wonderful orchestra, after all. I’ll give them full credit for a bang-on marvelous “Marching Band” passage, one of the most thrilling I’ve ever heard.

The Final Verdict

So it all boils down to the three recordings that impress me as giving Cockaigne its well-deserved due:

- Edward Elgar, Royal Albert Hall Orchestra, 1926: maybe not as polished as the 1933 BBC Symphony rendition, but bristling with life and vitality.

- John Barbirolli, Philharmonia Orchestra, 1962: altogether the no-brainer recommendation; lively, passionate, and gorgeously played.

- Jeffrey Tate, London Symphony Orchestra, 1991: a deeply personal and surprisingly intimate approach to a piece often treated as a mere showpiece.