You Drunken Sot

Now, don’t you go taking the article’s title personally; I don’t mean you. The title refers to the song “You drunken sot!” (Akh tï, p′yanaya teterya!) by the nineteenth-century Russian composer Modest Mussorgsky.

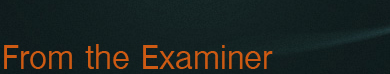

As Victor Borge quipped, Mussorgsky took his song’s title just a wee bit too literally and wound up diminishing more fifths than almost any other composer in history. That’s saying quite a lot; Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert were notably heavy drinkers although none was likely an alcoholic. Mussorgsky, on the other hand, was the real McCoy, booze-wise.

Mussorgsky in 1881, painted by Ilya Repin

That’s too bad, really too bad. Mussorgsky was an authentic diamond-in-the-rough genius with an amazing ability to translate text and vision into sound. Untrained, uncouth, unmindful of the niceties of composition, he created works which are nevertheless compelling in their elemental force, no matter how disfigured by poor structure or near-inept orchestration.

A thriving cottage industry for fixing and finishing Mussorgsky arose even during his lifetime. Rimsky-Korsakov, doyen of the loose confederation of composers eventually dubbed “The Five” (the others were Borodin, Cui, Balakirev, and Mussorgsky) did a lot of the fixing and finishing -- some would say too much of both. Rimsky-Korsakov had started out every bit as much of a rough-and-ready naturalist as his colleagues, all of whom professed indifference to formal conservatory-style training. Eventually he studied intensively on his own and wound up the very model of a spit-and-polish master, teacher of Igor Stravinsky and a thoroughgoing professional musician.

Rimsky-Korsakov worked over Mussorgsky’s fascinating but unruly compositions and left them in the state in which they are typically best known today. However, intrepid musicians have been taking a good, hard look at the unedited originals and are finding value in Mussorgsky's unpolished, intestinal crudity. Increasingly performers are choosing those originals rather than Rimsky-Korsakov's suave rewrites.

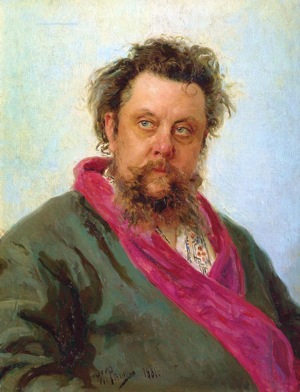

Viktor Hartmann's sketch for The Great Gate of Kiev, the finale of Pictures at an Exhibition

No work of Mussorgsky’s has received more editorial attention than Pictures at an Exhibition, albeit for a reasons other than fixing-up or completing; the work is both fixed up and complete as Mussorgsky wrote it. However, the original setting is for solo piano -- starkly effective, to be sure, but seemingly inadequate for the aural splendor of Mussorgsky’s imagination.

Transcribers have been creating orchestrations of the work since its first public performance (an abridged orchestration and not the piano solo). Most folks are familiar with only one of those orchestrations -- Ravel’s masterful 1922 transcription, rightly celebrated as one of the great collaborations in music history. It was an unlikely pairing: one participant fussy, twee, and finicky (Ravel) and the other elemental, crude, and instinctive (Mussorgsky). Their opposing personalities complemented, rather than cancelled out, each other and the end product almost seems like the work of a third composer -- one blessed with Ravel’s fastidious technique together with cajones the size of basketballs.

There are those who think that Ravel’s Gallic style wound up overshadowing Mussorgsky’s vodka-soaked Russianness. (There are also those who point out that three of the movements in Pictures -- Tuileries, The Market at Limoges, and Catacombs -- sport French settings, thereby rendering Ravel’s Gallicisms wholly appropriate.)

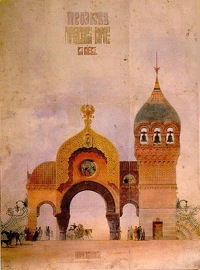

One of the folks who thought Ravel’s version inadequate was Leopold Stokowski, that astonishing conductor whose flair for orchestral color was matched only by his flair for unabashed showmanship. Stokowski’s transcription of Pictures -- written almost certainly with substantial assistance from the Philadephia Orchestra’s in-house arranger Lucien Cailliet -- is to date the only non-Ravel orchestration to have maintained a presence in the concert hall.

It’s shorter than most; Stokowski concluded that the French-themed movements were detrimental to the innate Russianness of the work, and so he excised both Tuileries and The Market at Limoges. (Catacombs is just too juicy to leave out, and besides, catacombs are hardly unique to Paris.) Stokowski also trimmed out a number of repetitions of the Promenade theme that interconnects the movements.

The Stokowski Pictures is marvelously effective on its own; the trick in listening is to avoid comparing it mentally to the Ravel. If I hear the opening Promenade with Ravel in mind, then my reaction is likely to be negative: hey, what happened to the trumpet? But if I take it entirely on its own (as far as that is possible), I discover a varied, exciting, and quite successful setting of Mussorgsky’s kaleidoscopic original.

Other transcriptions abound, if you’re interested in exploring. One of the niftiest ways to go about it is through the compilation version assembled by Leonard Slatkin, performed by the Nashville Symphony Orchestra, on Naxos. If you’d prefer to examine some of the orchestrations more fully, those of Sir Henry Wood, Ralph Funtek, and Vladimir Ashkenazy are easily available either as downloads or on CD.

The Stokowski version is easily available on record: Matthias Bamert conducts the BBC (Chandos) and José Serebrier conducts the Bournemouth Symphony (Naxos). My links are to CDs; downloads are easily available.

Leopold Stokowski

But I recommend coming to Davies Symphony Hall to hear the San Francisco Symphony play the Stokowski transcription, under the leadership of British conductor/composer Oliver Knussen, on April 16, 17, and 18.

I’ll be giving the pre-concert lectures for those concerts, for which I’ll be going through some of the various transcriptions available and playing excerpts that illustrate how different arrangers approached individual movements. I’ve also written the program notes for the Mussorgsky, which are available from the SFS website, or in printed form in Playbill at the concert.

Here’s the skinny on the concerts:

- Thursday, April 16 at 2:00 PM (pre-concert lecture at 1:00 PM)

- Friday, April 17 at 8:00 PM (pre-concert lecture at 7:00 PM)

- Saturday, April 18 at 8:00 PM (pre-concert lecture at 7:00 PM)

More info available from the SFS website, here.