Villa Lobos, Muse of Brazil

I have no desire to prove anything by dancing. I have never used it as an outlet or as a means of expressing myself. I just dance.

-- Fred Astaire

The quote above beautifully illustrates a truth about certain creative figures; they simply do what they do, without agendas. They just do it: they dance, paint, write, compose, sculpt, play, cook, etc.

There are, of course, those creative figures who are deeply concerned with personal expression or a sense of mission. That doesn't make them any better or worse; it's just a different approach.

I would put Wagner at the head of the list of purpose-driven composers, those who had a strong sense of mission. Other candidates would include Schoenberg, Bach (theologically, at any rate), or Beethoven.

But what about the "I just write" folks? Mozart wasn't quite as much of an unconscious natural as he is sometimes made out, but that sense of composing as a near-reflex activity is strong with him.

Like Astaire, whose dancing appeared to flow directly from the very substance of his body, Handel allowed music to pour out of him in a steady stream; he's definitely another.

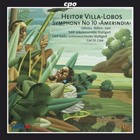

There may never have been quite as spontaneous and free-flowing a composer as Heitor Villa-Lobos, Brazil's finest gift to musical humanity. The man exhaled music the way most of us exhale carbon dioxide, in an unquenchable torrent of imaginative, colorful, and emotionally up-front compositions.

Heitor Villa-Lobos (1887-1959)

As one might expect, he was prolific as all get-out, but happily he avoided the humdrum punctilio that sometimes mars the work of other high-volume composers such as Martinu, Hindemith, or Milhaud. He wasn't a trail-blazer, particularly, but he was never dull. Passion and a sheer heady delight in sound itself are the trademarks of his work.

Villa-Lobos' Language

He was fundamentally a neo-Classicist composer who was strongly impacted by Debussy, Stravinsky, and the fauviste movement of the 'teens and 'twenties. His harmonic language makes full use of the panoply of early 20th century idiom: synthetic modes, pentatonicism, octatonicism, parallelism, expanded tonality. He was never particularly atonal; his was a gentle modernism that never lost a love of pure sound.

Although Villa-Lobos is generally considered a nationalist composer, his overall language was pan-European. The article in Grove's puts it quite well:

Although matching the basic premises of the nationalist aesthetic agenda of his era, his own nationalism was kaleidoscopic to correspond to his numerous creative sources, many of which sublimated the simple incorporation of indigenous musics. In effect, he created his own individual symbols of identity and made them acceptable as uniquely national.

Today's article focuses on three large bodies of Villa-Lobos' output, all predominantely instrumental: Bachianas brasileiras, Chôros, and the symphonies.

Bachianas brasileiras

There are nine of these all told, each paying homage to J.S. Bach while at the same time exploring a fusion of Baroque harmonic and contrapuntal procedures with the idioms of the mid 20th century. Typically each is in the form of a suite with several movements, some of them with dance titles such as Modinha or Miudinho, others with more overtly Baroque names such as Aria, Toccata, Giga, or Fugue.

Although a fair number of the Bachianas brasileiras are scored for full orchestra, the full set displays a wide range of instrumental possibilities, including voice. #5 is easily the most famous of the set, its hauntingly beautiful soprano vocalise in the first movement giving way to a Martelo dance of the finale, all accompanied by an orchestra of 8 cellos.

.jpg) Only #s 7 and 8 were originally written for full orchestra; the popular #4 was originally for solo piano and was later orchestrated. Several are written for strings alone -- #s 1 (cellos only) and 9, whereas #6 is a duet for flute and bassoon.

Only #s 7 and 8 were originally written for full orchestra; the popular #4 was originally for solo piano and was later orchestrated. Several are written for strings alone -- #s 1 (cellos only) and 9, whereas #6 is a duet for flute and bassoon.

All together, the Bachianas brasileiras make a wonderful introduction to the world of Villa-Lobos, in their melodic beauty, quirkiness, rich harmonies, and inventive orchestration.

An excellent edition of the complete Bachianas brasileiras can be found on Naxos, with Kenneth Schermerhorn conducting the Nashville Symphony Orchestra.

Chôros

If the Bachianas brasileiras are the best-known of Villa-Lobos' instrumental music, the Chôros are the heart of his output. They are the most overtly nationalistic of his works, inspired as they are by the improvisational music of Rio de Janeiro and other Brazilian cities.

There are 12 Chôros in all (originally 14, but the last two are unfortunately lost), plus an "Introduction to the Chôros" for guitar and orchestra, and an unnumbered one for violin & cello.

The instrumentation varies widely, from solo guitar (#1), solo piano (#5), through duos and small chamber groups (#s 2, 4, 7), to settings for downright gigantic orchestral forces sometimes including chorus (#s 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12).

Villa-Lobos employed Brazilian folk instruments in some of them, particularly #6 (coco, roncador, tambu-tambi, cuíca, recoreco). Some might involve vocalizing from the orchestra (#9) here and there.

How to describe the impact of the Chôros? Kaleidoscopic, certainly; technicolor evocations of a lushly beautiful country, yes. Orchestrally they are often hair-raising showpieces. In length they run anywhere from a few minutes to over an hour (#11 for piano and orchestra).

Typically they are episodic works, one idea giving way to another in a kind of improvisational free-association style, very much in keeping with their original roots.

Fortunately for us, good recordings abound, but none better than John Neschling's complete series with the São Paulo Symphony Orchestra, captured in utterly wonderful audio by Swedish label BIS. The set comes in three separate volumes:

- Volume 1: Chôros Nos. 5, 7, 11

- Volume 2: Chôros Nos. 1, 4, 6, 8, 9

- Volume 3: Chôros Nos. 2, 3, 10, 12

Symphonies

Although Villa-Lobos wrote 12 symphonies in all, one (#5) has been lost. These imposing works have yet to receive their due, or even very much attention for that matter. They're rarely performed or recorded. What little opinion about them that exists seems to hold that they are not well constructed symphonically, but are instead yet more examples of Villa-Lobos' purely flowing compositional style.

Well, maybe. Whether or not they are constructed according to the precepts of classical symphonic structure is, to my mind, not particularly important. That kind of attack has been made ad infinitem against innumerable composers whose compositional practices don't match up to somebody's Beethovenian/Mozartian/Haydnesque ideal.

In fact, they represent an astonishing musical treasure chest just waiting to be explored by the intrepid. Fortunately for us, they can be explored thanks to the splendid efforts of conductor Carl St Clair, the SWR Radio-Sinfonieorchester Stuttgart, and those fine folks at CPO. They began a cycle in 1999, and completed it just a year ago.

Thus all of the Villa-Lobos symphonies are available in hellzapoppin' performances and first-rate audio:

- Symphonies 1 & 11

- Symphony No. 2; New York Skyline Melody

- Symphonies 3 & 9; Overture to William Tell

- Symphonies 4 & 12

- Symphonies 6 & 8

- Symphony No 7; Sinfonietta No 1

- Symphony No 10 "Amerindia"

If I may be so bold as to suggest an entry point to nearly eight hours of music, consider Symphony No. 9 for your first. It's a wonderful blend of neo-Classicism with passionate romanticism, in an opulent orchestral setting. Despite being tightly constructed and succinct it nonetheless pulsates with Villa-Lobos' hedonistic, unrestrained passion.

When you're ready, launch into Symphony No. 10 "Amerindia", a spiritual oratorio manquée sporting, among other luxuries, a Mahlerian slow movement of 31 minutes duration. Chorus, soloists, and orchestra together make this one a delectable soundfest spectacular that culminates in a deeply-moving hymn of joy.