Elgar's Dream Journey

October 3, 1900 witnessed one of music history's most unfortunate premiere performances, ranking right up there with the opening-night fiasco of The Barber of Seville. A behind-schedule composer had failed to deliver the complete manuscript until a mere ten days before the performance; the chorus master had passed away suddenly; the new chorus master had been lured out of retirement and showed little empathy for the work; the vocal soloists were poorly chosen; the music was exceedingly difficult to perform; the frustrated composer publicly dissed the soloists at the dress rehearsal.

It was one of those productions -- a stageful of victims assaulted by The Piece from Hell, everybody confused, resentful, and desperately in need of more preparation time, the composer snapping at everyone in range, the whole marked by a feeling of impending doom.

In the movies, it would have all drawn together at the last minute.

But it didn't. The Dream of Gerontius laid an egg, leaving its composer Edward Elgar in near despair and venting his spleen in no uncertain terms:

I have worked hard for forty years &, at the last Providence denies me a decent hearing of my work: so I submit--I always said God was against art & I still believe it...I have allowed my heart to open once--it is now shut against every religious feeling & every soft, gentle impulse for ever.

Despite the miserable debut, a few selected listeners recognized the work's quality. Subsequent performances -- particularly those under Richter with his own Hallé Orchestra -- established Gerontius as a milestone of English choral writing, in some ways a perfect conclusion to English romanticism in the dawn of a new century.

Sir Edward Elgar

Nonetheless, Gerontius's journey bodes rough sailing for many 21st-century travellers. The text is the problem. Cardinal Newman's blockbuster verse epic about death, the afterlife, and the possibility of salvation is a turgid morass of preachy platitudes bleated forth in an unintentional parody of Jacobean English. Reading it is a protracted ordeal guaranteed to confirm one's darkest suspicions about smarmy Victorian expressions of public piety.

Try this on for size:

Thou speakest mysteries; still methinks I know

To disengage the tangle of thy words:

Yet rather would I hear thy angel voice,

Than for myself be thy interpreter.

Yecch.

Sidenote: thee and thou weren't necessarily churchy in Shakespeare's English -- in fact, they were typically used when speaking downwards, such as a parent to a child or a master to an apprentice. They acquired their patina of sanctimoniousness via the popular "King James" translation of the judaeo-christian texts.

Elgar's contemporaries were thoroughly distressed by the libretto, but not necessarily for its glutinous language. They didn't like all that Catholic stuff; after all, the English of 1900 were mostly solid CofE clients -- although the tide of secularism was soon to break that particular stranglehold -- so Catholic Elgar's passionate setting of Newman's frothy sanctimoniousness elicited squirmy dismay.

Cardinal John Henry Newman, author of The Dream of Gerontius

Nowadays audiences are much more likely to find the whole thing worthy of pantomimed puking; references to Mary, purgatory, or saints simply dissolve into the overall vat of aversion for such blatant and highfalutin' Victorian piety. (Americans are far more likely to become queasy around Gerontius than the British, for whom the work is a national monument.)

But musically The Dream of Gerontius is a triumph of imagination, passion, and compositional skill. The trick is to listen past the saccharine snivelling of the text -- insofar as that is possible -- and focus on Elgar's magnificent blending of Wagnerian techniques with his own vivid personal style. Gerontius works gloriously on its own terms, and in a fine performance can be an unforgettable experience.

Gerontius tells the story of a old man's death, his transformation into the afterlife, and his arrival in purgatory in expectation of eventual salvation. A Wagnerian orchestra and supersized chorus are joined by three soloists: Gerontius himself, a tenor; a mezzo-soprano angel, and a bass-baritone who sings the dual roles of the priest who sends Gerontius to the afterlife and the "Angel of the Agony". It is a through-composed work with only a single break between the two parts.

Along the way it offers some downright magnificent stuff: Gerontius's dying prayer, the Priest sending Gerontius to heaven, the angel's exquisite duet with Gerontius, the energetic chorus of demons, the softly compassionate lullaby of the ending. Gerontius repays repeated hearings with lavish dividends; the various leitmotivs serving as structural signposts become ever-more audible, the magical orchestration exerts increasing fascination, and Elgar's elegant pacing becomes increasingly impressive. What may have initially seemed a musty relic of a bygone age is revealed as a music drama of absolute conviction, compelling and vibrant.

Elgar was faced with the difficult task of portraying a brief glimpse of a deity -- similar to the challenge faced by Stanley Kubrick in 2001: A Space Odyssey in regards to the alien civilization that has been shepherding humanity towards a new level of evolution. Kubrick's solution was the better of the two: he did it all via indirection and never actually showed us anything. Elgar went in for a short, very loud WHAP. It works as well as can be expected under downright impossible circumstances.

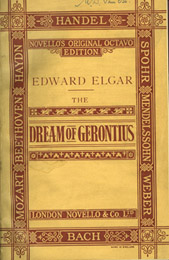

An original edition of Gerontius

Gerontius has been recorded far more times than one might expect. We even have Elgar himself conducting excerpts. I would never profess to expertise on the subject of Gerontius recordings; try this resource for a solid coverage of recordings up to the mid-1990s.

I have my personal favorites, however. They are:

- Benjamin Britten conducts the London Symphony, with Peter Pears as Gerontius, John Shirley-Quirk as the Priest/Angel, and Yvonne Minton as the Angel. One great English composer interprets another, the elderly Pears was perfectly cast in the role, Shirley-Quirk is wonderfully magisterial, especially in the Part 1 finale Go in the Name of Angels, and Yvonne Minton sings the Angel as beautifully as could ever be imagined.

- Sir John Barbirolli conducts the Hallé Orchestra, with Richard Lewis as Gerontius, Kim Borg as the Priest/Angel, and Dame Janet Baker as one of the most memorable Angels on record. You have to deal with the Finnish Borg's weird English diction, but vocally he's glorious.

- Sir Adrian Boult conducts the New Philharmonia Orchestra, with Nicolai Gedda's unforgettable Gerontius, Robert Lloyd as the Priest/Angel, and a very fine Helen Watts as the Angel.

Among modern recordings, the Hallé Orchestra under Mark Elder has been receiving raves; you can get it from ArkivMusic, or Presto Classical in the UK.

Gerontius is now public domain, and the score is easily available for free via the Internet library IMSLP. The Dover reprint is now out-of-print and exorbitantly priced; here's a link to Amazon. You can get a piano-vocal score for about $30.00 from SheetMusicPlus, or a study score for $50.00; here's the page for that.