An Earthsong for Everyone

As the San Francisco Symphony releases Das Lied von der Erde, the next-to-last installment in the complete Mahler series, I'm moved to think about the work itself and its near-century of performances, both live and recorded. (I'll discuss the SFS recording itself in a future post.)

The Song of the Earth fuses its disparate elements into a single, coherent whole — despite the far-flung nature of its individual components. Probably the work shouldn't hang together.

The Song of the Earth fuses its disparate elements into a single, coherent whole — despite the far-flung nature of its individual components. Probably the work shouldn't hang together.

So much could have damaged it beyond repair: the text's confusing cross-cultural journey from Chinese through French through at least two layers of German; Mahler's daring synthesis of massive symphonic forces as support for intimate lieder; a last movement as long as the previous five all together; two separate vocal soloists, one either male or female; and extensive chinoiserie, only too often ill-fitting and cloying in Western European music.

I rather wonder if any other composer could have pulled it off. Just the quasi-Asian elements alone could have been fatal; European composers were not exactly multicultural cosmopolitanites as a rule.

For every Debussy conjuring up a mystic Pagodes there was a Ravel denigrating an entire culture (unintentionally, let us hope) with the cutsey-poo Laideronnette, Empress of the Pagodas. Puccini got away with it in both Madama Butterfly and Turandot primarily, I think, because both shows are such glorious primary-color comic books, thus there's really no point in taking offense at those echt-Chu Chin Chow portions of both scores. (Although sometimes they rankle me anyway.)

At least in this one fellow's opinion, faux-Chinoiserie in Western music is more often than not a musical and a cultural disaster. Only when Western composers such as Lou Harrison were equipped fully to embrace Asian idioms that fusion without dishonor could be achieved.

Since he was setting Chinese poetry in Das Lied von der Erde, it is understandable that Mahler would incorporate some Asian flavoring in both his orchestration and his harmonic-melodic materials.

I've always admired his sensitivity and taste in this regard; overtly Asian elements are mostly absent from the opening Das Trinklied von jammer der Erde, provide only the lightest seasoning in Der Einsame im Herbst, then only come really into play in the trio of lighter middle movements Von der jugend, Von der Schönheit, and Der Trunkene im Frühling. In the consummating half-hour expanse of Das Abschied the Asian elements float in and out of the texture, sometimes overt, other times subtle. It works.

I don't normally think of Mahler as a composer of restraint, but oddly enough that's the only word that will do when describing the orchestration. Even odder, Das Lied calls for a gigantic orchestra. That massive collection of instruments, however, is treated rather like a chamber-music combinatorial ensemble, in which small groups of instruments are assembled together, disassembled, and recombined with other instruments in a near-constant shift of tonal color. Even the overall changeability of the texture could have gone overboard; the whole might have become impossibly fragmented, as though aimed at folks with sonic attention-deficit disorder. Instead, it works.

Two singers, yet no obvious change of narrator. The demanding songs are split between two soloists, allowing the singer of Das Abschied at least some rest before launching into one of the longest lieder ever written. It works.

.jpg) That strange imbalance between the sixth-movement Das Abschied, as long as the previous five movements all together, transforms an orchestrated song cycle into a symphonic work, providing a balance to an opening movement which is structured in a creative variant of traditional sonata form. Thus even if we aren't consciously aware of the work's symphonic roots, we respond to the essential rightness of that extended final movement. Boy, does it work.

That strange imbalance between the sixth-movement Das Abschied, as long as the previous five movements all together, transforms an orchestrated song cycle into a symphonic work, providing a balance to an opening movement which is structured in a creative variant of traditional sonata form. Thus even if we aren't consciously aware of the work's symphonic roots, we respond to the essential rightness of that extended final movement. Boy, does it work.

In my own musical history The Song of the Earth holds a special place; an early experience being revolted by Mahler's First Symphony came very close to souring me on his music forever, but through it all Das Lied remained the one Mahler work I loved. Eventually I began dipping back into Mahler's symphonies (the SFS series has served as a fine encouragement), and much of my earlier aversion has evaporated.

Das Lied von der Erde has received a fair number of truly exceptional performances on record since its 1911 premiere. Certainly Bruno Walter ranks first place on the honor roll; a Mahler protegé and proselyte, he conducted the first performance and went on to record the work about a half a dozen times throughout his career, starting in 1936 with the first ever complete recording.

Walter's rendition in 1952 with the Vienna Philharmonic stands rightfully among the legendary recordings of the century. That isn't to say that it's the finest performance of Das Lied, far from it. Inadequacies crop up throughout, in fact.

Walter's rendition in 1952 with the Vienna Philharmonic stands rightfully among the legendary recordings of the century. That isn't to say that it's the finest performance of Das Lied, far from it. Inadequacies crop up throughout, in fact.

But the post-war Vienna Philharmonic, despite some technical shortcomings, plays its heart out for Walter (who, we should remember, was compelled to go into exile during the Nazi years). The soloists are the superb tenor Julius Patzak, a great pre-war star of the Vienna Opera, and contralto Kathleen Ferrier, one of the most beloved singers of her generation.

When you get down to it, Ferrier's contribution is really the reason for this recording's exalted status. Quite a few folks who hear her voice nowadays wonder what the fuss was all about; plummy, open-throated British contraltos of this type definitely belong to a time and a place, neither of which intersects with us.

Ferrier was also nearing the end of her sadly short life at the time of this recording, and here and there physical strain can be heard. No matter. Time capsule from a vanished era or not, the Walter/Ferrier/Patzak rendition remains deeply moving, beautifully placed, intelligently and compassionately performed.

Another celebrated recording probably shouldn't have worked; it exemplifies 1960s studio artifice at its most over-produced. Started in February of 1964 with one of the vocal soloists, it was continued in November with the other. After those session, the orchestra disbanded and was reconstructed — and the recording was completed in July of 1966. The soloists were never together during the sessions (and the tenor in fact died two months after 1966 session.)

And yet Christa Ludwig, Fritz Wunderlich, Otto Klemperer, and the (New) Philharmonia Orchestra bring off one of the grand ones. From listening you'd certainly never pick up that two years elapsed between one track and the next.

And yet Christa Ludwig, Fritz Wunderlich, Otto Klemperer, and the (New) Philharmonia Orchestra bring off one of the grand ones. From listening you'd certainly never pick up that two years elapsed between one track and the next.

It's a significantly different experience from Ferrier-Patzak-Walter; Ludwig, in particular, was a much more technically accomplished singer than Ferrier and brings a soaring majesty to Das Abschied, and without a shadow of a doubt Wunderlich sets an all-time standard of excellence. Oh, the performance (and the recording) is overall a bit iron-jawed and shellacked. Nonetheless, its fine reputation is well deserved.

.jpg) We don't normally think of Fritz Reiner as a Mahler guy; we do have a fine 4th Symphony from him, to be sure. However in The Song of the Earth he helmed his incomparable Chicago Symphony Orchestra, with Maureen Forrester and Richard Lewis in a sumptuous RCA "Living Stereo" recording that belongs on anybody's short list. Perhaps neither of the soloists have quite the star power of Ludwig, Wunderlich, or Ferrier, but they were nonetheless class-A artists who turned in exceptionally fine performances.

We don't normally think of Fritz Reiner as a Mahler guy; we do have a fine 4th Symphony from him, to be sure. However in The Song of the Earth he helmed his incomparable Chicago Symphony Orchestra, with Maureen Forrester and Richard Lewis in a sumptuous RCA "Living Stereo" recording that belongs on anybody's short list. Perhaps neither of the soloists have quite the star power of Ludwig, Wunderlich, or Ferrier, but they were nonetheless class-A artists who turned in exceptionally fine performances.

About Reiner and the Chicago, well — what is there to say? The man might have been an obnoxious tyrant, and possibly overrated as a conductor, but there's no denying the beauty and precision of that astonishing musical instrument, the Chicago Symphony of the 1950s. Principal oboist Ray Still's solo at the opening of Der Einsame im Herbst absolutely melts the heart.

From a live concert of February 27, 1970 we have one of the all-time glorious renditions from Rafael Kubelik, Waldemar Kmett, Janet Baker, and the Bavarian Radio Symphony. Baker sang the work gorgeously with other conductors, but there's something especially beguiling about this particular performance, and Kmett turns in one of the most expressive readings in history.

All of the above recordings share the use of male and female soloists, but a tenor/baritone combo is perfectly normal and fine for this work. Two baritones in particular have made the work their own: Dietrich Fisher-Dieskau and Thomas Hampson.

All of the above recordings share the use of male and female soloists, but a tenor/baritone combo is perfectly normal and fine for this work. Two baritones in particular have made the work their own: Dietrich Fisher-Dieskau and Thomas Hampson.

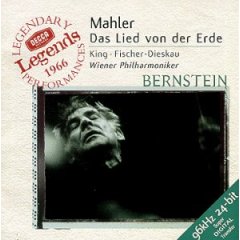

Fisher-Dieskau recorded the work with a number of conductors and orchestras (and vocal partners), but one of the most memorable pairs him with James King, Leonard Bernstein, and the Vienna Philharmonic. Oh, Lenny's Mahler isn't to absolutely everybody's taste — neither is Fisher-Dieskau's tendency to chomp — but this Song is a thing of wonder. (Another recording pairs Fisher-Dieskau with Fritz Wunderlich; talk about a meeting at the summit.)

Thomas Hampson (who appears on the new SFS recording) has performed the work on record with Sir Simon Rattle and the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, paired with tenor Peter Seiffert. (I'll speak a bit more about this recording in a future post.)

Rainer Riehm worked up a chamber version of Das Lied (based on some marginal notes from Arnold Schoenberg) which has been set to disc by a number of ensembles; a particularliy interesting one comes from Osmo Vanska and a group drawn from the Lahti Symphony.

I'll have an article about Michael Tilson Thomas's new recording of Das Lied von der Erde with Stuart Skelton, Thomas Hampson, and the San Francisco Symphony on September 9, the day of the recording's release..